Bill stood up and pocketed his handkerchief, looked up at the grey sky, and watched three turkey buzzards glide a low, loose circle directly overhead and, in the distance, high above the lemon grove to his right, he could just make out a small delicate-looking helicopter floating in and out of the clouds, like a dragonfly.

The body at his feet, in the shallow ditch, was a dump job. He knew that. He glanced around. “Like a giant laid the poor bastard down in the dirt.” He talked as if he were accompanied by an attentive but quiet companion. To his left, on the east side of the ditch, was the small dirt lot, no tire tread marks, County Road 27 just on the other side of it. West of the ditch, Grant Parson’s Meyer lemon grove, row upon row upon row, the size of a small town.

It had been Sugar Burkson, in fact, Parson’s reticent chief cultivator, who’d discovered the body just before sunup. He’d called Parson instead of the police and Parson called it in. Earlier in the morning, Bill had asked him, more in passing than to get information, “What you figure, Sugar?” His only comment was “Fuck if I know.”

Bill walked back to his truck in the burgeoning morning heat, looked at his watch: eight-thirty. He opened the toolbox in the bed of his truck and pulled a can of Busch Light out of the cooler hidden inside. He listened to the squirrels bark and squee in a nearby oak tree. The first few gulps were hard to get down and he almost heaved, but by the time he got to the bottom of the can, there it was: the slow spread of soft golden interior light, and he began to feel right again. He chucked the can, empty but for an ounce or so of swill, in the direction of the squirrels. “Reckon that’s Walter Pound’s charred corpse?” he said to his phantom partner.

“Ought not to litter, Sheriff,” said Deputy Lloyd Barnes as he approached Bill. “It’s a five hunnerd dollar fine in Highlands County.” He smiled at the sheriff, stopped in front of him. “Little goddamn early for an adult beverage, ain’t it?”

Bill’s drinking was no secret to anyone, but most people, out of respect, didn’t give him any shit about it. Together they walked back to the shallow dip in land between the lot and grove where the body lay. Bill wasn’t sure he wanted to tell his deputy what he thought.

Lloyd nudged a black leg with his boot and a crackling sound issued from it.

“Crispy fucker.”

“Quit kicking at it, boy.”

Barnes glanced around, pulled a can of Copenhagen from his shirt pocket, tapped it three times.

“Right off the bat, I got some ideas.”

Walter Pound was Lloyd’s cousin. They were, in fact, first cousins. Walter’s daddy, dead for some time now, had been Lloyd’s uncle. If this body was Walter Pound’s, Deputy Barnes would have some opinions on the matter, and Bill wasn’t quite ready for that.

“Do tell.”

“Even without knowing who this dead bastard is, I’d start with Evil Dead.” Lloyd squinted an eye at the sheriff as he put a pinch of dip into his mouth and tongued it into place. It began to lightly rain, just more than a mist.

Lloyd squatted down and took a closer look. “Who are you?” he whispered.

“Plausible,” said Bill. Evil Dead were something of a scapegoat for Lloyd. Still the biker gang had crossed his mind, as well. Of the three in the area, they were the most brutal, and they were responsible for many horrors committed in Durdin. Walter had been mixed up with them. But something told him this had not been done by Evil Dead. This, to his mind, was the result of hate, not business—maybe even deep, familial blood hate, the kind that many of the Pounds and Baggotts had for one another. Things had been quiet between the two families for a while, but relations always soured every few years, and when they did, shit would go down.

Lloyd looked up, the way the sheriff had earlier. The rain had intensified.

“Almost seems like the son of a bitch was dropped out of the fucking sky, don’t it? But there’s no impact impression anywhere.” Lloyd spat a brown stream of dip, then wiped his mouth. “What you want me to do? I’d love to go put the fear into some dipshit bikers.”

“Just hang tight for now.” He wanted to ask him if Enid, Walter’s wife, still lived in Sahwoklee, two counties over, but didn’t want to get Lloyd’s mind working. If he asked about Enid, Lloyd would no doubt make the leap to the possibility of the body being Walter’s, if he hadn’t already. “For now, let’s just get out of this rain.”

Thirty-five years ago, Walter Pound fell out of a cedar tree on the Durdin Elementary School playground and scraped his elbow. Mrs. Hillman, their kindergarten teacher, an ordinary townswoman, ignorant of backwoods feuds and ways, requested Enid Baggott walk Walter to the school clinic. Enid held his hand the whole way there, waited while the nurse fixed him up, and walked him back. At the age of five, they were barely aware of their own last names, much less any tension between their families, and from that day on, Walter thought often of Enid, despite what he would later realize about their families’ extreme dislike for one another. Some sixteen years later, at Lillian and Dill Talbert’s wedding, something drew them together, and they stayed tangled up.

As Sheriff Bill Register pulled off the small dirt lot of Parson’s lemon grove, he believed, but could not yet prove, he’d found evidence of the grim opening salvo in a new interfamilial skirmish.

Upon leaving Parson’s grove, Lloyd decided he’d not “hang tight,” as the sheriff had told him to do. Instead, he found himself turning onto Firebreak Road, a few miles south on twenty-seven, just outside Durdin city limits, and pulling into the chalky white lot of the Evil Dead Clubhouse. The building had been a VFW, but the bikers bought the building a few years back when the VFW moved to a new location closer to town. Two vehicles sat in the lot: a Harley with a confederate flag fuel tank and a black Ford F‑150. The truck was always in the lot. The block building was still white with red trim, but there was a narrow sign over the door that read

EVIL DEAD m.c. est. 1945.

If this is Hell, it’s really not that bad.” ‑Duchess of Durdin

Lloyd could smell fire, which reminded him of the charred body in the grove, and he felt a wave of nausea, but forced it down. As he approached the back of the building, he heard voices, and as he turned the corner he saw another motorcycle, an old Triumph, all black and chrome. Just beyond the bike, a smoker and two men standing next to it. Lloyd knew better than to sneak up on these men, so he yelled “Boys!” and waved as he came into view.

“Deputy dog,” growled the big one manning the smoker. Doug Crenshaw and Lloyd had grown up together, had even been friends in their early teens. Doug was not a Baggott, but he’d grown up swarmed with them. When Doug had joined up with the Evil Dead he’d tried to recruit Lloyd. But Lloyd was set on prowling through Southeast Asian jungles instead. The second man, a skinny tweaker named Spider, watched, as Lloyd approached.

“Getting an early start,” said Lloyd, pointing at the smoker.

“Takes about eight hours, if you do it right. Gives you a reason to start drinking early, too.” Doug raised his Budweiser and took a swig. He was a big boy, at least six feet, probably two-fifty, but not as big as Lloyd. The one watching was thin and short but wiry.

“Man, that smell…” Lloyd took a few steps closer. The intensity of the smell was about to put him over the edge but puking in front of these two was not an option.

Doug opened up the lid and dense, blue-grey smoke tumbled up from inside.

“Take a look.”

Lloyd stepped into the proximity of the two men and stood next to the smoker, next to the big man, and the spidery one moved in on Lloyd’s right.

“Goddamn,” said Lloyd.

Doug drank the rest of his beer and hurled the bottle into a metal drum close by. He closed the lid on the smoker and Lloyd stepped back, and so did the twitchy one named Spider.

“Was wanting to ask you,” said Lloyd.

“Here it comes,” said the big one. “I knowed you weren’t paying us a social visit.” He looked at his partner.

“It ain’t like that.”

“It damn sure is like that. It’s always like that. Any-damn-thing occurs and you or Bill comes peeping around the corner. What’s it this time? A purse-snatching?”

“Fine,” said Lloyd. “It is like that. No sense in playing make believe.” Lloyd fished out his cannister of Copenhagen, put in a dip, spit off the few grains of tobacco stuck to his bottom lip. Somehow this helped with the nauseating feeling from the smoldering pork butt. “Y’all villains, big man,” he continued. “Something bad happens, I come talk to the bad guys.”

The wiry one took a big step inward.

“You better settle the fuck down,” said Lloyd, with his right hand out in front of him. The man stopped

Doug smiled and nodded at the other.

“Lloyd Barnes, Vietnam badass!”

The thin one chuckled.

“You might be able to scare teenagers and little old ladies talking like that, but you ain’t shit here. We’ll knock you on the head and drop your ass in a phosphate mine, bury you in an orange grove, come back and eat some barbeque. Ain’t no thing to us.”

“Speaking of groves,” said Lloyd. “Found a burnt-to-a-husk bastard just north of here in a lemon grove. Just set down in the ditch like god laid him there. You wouldn’t by chance know anything about that, would you?”

“Sounds gruesome—but then, being a war vet, you seen all kind a shit, ain’t you? Dead babies and whatnot.”

Lloyd spit a deep brown gob at Doug’s foot.

“Look here,” said Lloyd. “You and your methhead pal hear anything you let me know. I’ll be back and I’ll be expecting a fucking anecdote or two.”

No one spoke. Lloyd touched the brim of his hat and turned his back on the two men and walked back to his truck.

Back at the station, Bill called Sahwoklee County Sheriff’s Office and talked to deputy Ben Lincoln, acting sheriff. Bill’s counterpart in Sahwoklee, Sheriff Frank Newsome, was six-months retired and had not yet been replaced, so the erstwhile deputy had taken over. Lincoln, all knew, would assume the role of sheriff officially once the county commissioners got used to the idea, but that was going to require a brief “mourning” period, as Frank had characterized it to his nephew Ben.

Bill asked Ben about Enid, Walter’s wife. Ben confirmed that Enid did, to his knowledge, still life in Sahwoklee County—presumably the small town of Cortez.

“As you know, she reported Walter missing three days ago. But I ain’t laid eyes on her drunk ass in a while. No telling where she might be.”

“As I know? I don’t know shit. You ain’t gone looking for Walter?”

“Not actively. Who gives a shit about Walter Pound—other than Enid? And I told your boy Lloyd to tell you about Walter when he called yesterday asking about Bradford’s cattle gone missing.”

Bill told Ben about the body in the lemon grove and his theory on who it might be.

“Lloyd did tell me about Enid’s report,” said Bill, lying to save face. “I must have forgot. Old age. Think I should talk to Enid though,” he added.

“Have you ever talked to Enid, sheriff? She ain’t exactly a sparkling conversationalist. And I’ll be honest, she’s smart as a snakebite, knows what to say and how to say it and has fun doing it. Likes toying with assholes like us.”

Bill told Ben that he had talked to Enid before, several times, and that he knew how to deal with her. When Bill hung up with Ben, he sat in his chair and tried figuring how to move ahead until he felt the heaviness of his fading beer buzz and drifted off.

When Bill woke he had a slight headache but he felt surprisingly rested. It was only ten o’clock. Let’s see, he thought. Take about forty-five minutes to get to Cortez. Drive around Sahwoklee for an hour or so, see what I see. Get back by about one or two. He stood up and patted at himself, looking for something to look for. Debbie Creel, his secretary clip-clopped into his office.

“Nice nap, Sheriff?”

He grunted.

“Medical Examiner called. Parson’s grove body being examined as we speak.”

“Thanks, Deb.”

She nodded and stood there watching him look around his office.

“You all right, Bill? I don’t like it when you’re all quiet like this.” Bill was always quiet, and she knew it.

“I’mma ride out to Sahwoklee.”

Debbie sighed. “This one’s got biker stink all over it, don’t you think?”

“It’s plausible.”

“I’d say a damn sight more than plausible. Who else could have done something like that? Could be Cuban mob—Tampa. Just dropping a body off ‘in the boonies’ or something.”

He smiled and nodded and touched Debbie on the shoulder on his way out.

“You see Lloyd, tell him to radio me, please, will ya, Deb?”

Debbie followed him out to his truck and knocked on his window. Bill rolled it down.

She whispered: “Could be a Pound-and-Baggott thing—that burned up body. That’s what you’re thinking, Bill. I bet it is, ain’t it?”

He winked at her.

“Any thoughts on whose body it is?”

He put the truck in reverse.

“Greedy old bastard,” said Debbie and she stepped away from the truck.

As Bill Register pulled onto the road, the fact that Enid had reported Walter missing pressed down on him. This is something, he thought. The distinct possibility of a Pound man found burnt up in a lemon grove. Could be a Baggott that done it, could be someone else. More than a few folks hated Walter enough to want him dead. Even, as Deb stumbled on, Cuban mob and affiliates. Even, as Lloyd had suggested, Evil Dead. It was even possible that Bradford’s missing cattle figured into things somehow. Anyone of consequence in the crime world on this whole damn peninsula has had, at some point, a reason to at least want the tar beat out of Walter Pound. Also, may not be that fire was what killed him. The burning could be post-mortem. Could be they burnt him up to cover up evidence. Highly possible. What, he thought, would Lloyd do if this all turns out to be true? What if that is Walter Pound’s body?

Back at the station, Lloyd was virtually accosted by Debbie Creel.

“You at Parson’s with Bill this morning?” she said as Lloyd sat down at his desk chair. She knew the answer.

“Yes, ma’am.” Unlike Bill, Lloyd would tell her all he knew, he usually did, but he also enjoyed stringer her along.

“What you reckon happened to that poor soul, Lloyd?”

“Well. Ms. Debbie, I figure he was burnt up.”

“No shit, Lloyd. I mean—who you think it is that done it?”

“Can’t say. Evil Dead, likely.”

“Interesting,” said Debbie.

“Why’s that?”

For the same reason as the sheriff, Debbie didn’t want to say too much to Lloyd about what she thought, about who she thought the body belonged to. If he’d brought up on his own the possibility, she’d have been more than happy to discuss possible scenarios with him—but she didn’t want to be the one to plant the idea in Lloyd’s head if it wasn’t already in there.

“No—it’s just that that makes sense. Any idea who it is—the body?”

“Come on out with it, Debbie. I know your minds working.”

She picked up a mug from earlier that morning with about an ounce of cold coffee in it and swirled it once then walked it over to the little stainless-steel sink in the corner and dumped it out and ran some water into it.

“Hell, what do I know, Lloyd. You the one been out there.”

He sighed, took off his wide-brimmed deputy’s hat and set it on his desk, looked down at his left hand.

“I do know for a fact that Enid reported my piece of shit cousin Walter missing a few days ago. Not ready just yet to mention this to Bill. Maybe he already knows. Maybe he doesn’t. But that’s family business.”

“I’ll be damn,” said Debbie. She could barely contain her delight at Lloyd’s mention of Walter and Enid. “This here—I think you’re right, Lloyd. This ain’t no bikers done this….How’d you know about Walter? Sheriff didn’t say nothing about that.”

“He tell you everything he knows, does he?”

She just looked down, then over at the wall.

“I called yesterday and talked to Ben, over in Sahwoklee, about a lead on them Brahmans gone missing and he told me—asked me to relay to Bill that Enid had reported Walter missing. I did not relay that message to Bill.”

Debbie nodded.

Lloyd continued: “Walter missing. Burnt-up Walter-sized bastard this morning. Don’t take too much intellect to sort out the possibilities, does it?”

“Well, Bill talked to Ben hisself just before he left earlier.” Debbie patted at the side of her head. “Whose cattle was that gone missing?”

“Them was Leon Bradford’s Brahmans.”

Leon Bradford, Debbie knew, was married to a Baggott woman. About fifteen years ago, he and Michaela Baggott, Enid’s cousin of some variety, got spliced up on the property Leon had bought a year prior for cattle grazing. It had been a big party, over a hundred people in attendance. A Baggott marrying someone wealthy like Bradford was a big deal. Debbie had been there. Kurt Bignall, the grocer, had asked her to go with him. Debbie did not like Kurt much, but she did like weddings, so she’d accepted Kurt’s invitation. She asked herself, would Walter Pound be dumb enough to steal Brahmans from Leon Bradford—and would Leon be bold enough to kill Walter for doing it? Lloyd must have read these thoughts on Debbie’s face.

“Debbie, Walter’d be crazy enough to steal Leon’s cattle, wouldn’t he?”

She told him yes, she thought he would.

Bill pulled into the dirt lot at Fuzzy’s, looked around, saw one other vehicle, a white Ford F‑150. There was a chained dog lying in the shade off to the left side of the door. He knew the dog but couldn’t call its name. The dog raised its head when Bill slammed the truck door, watched him walk all the way up to the entrance. There, again, was a light rain. But, as Bill stopped to look at the sky, he noticed a dark, almost purple shelf cloud to the northeast.

Bill went straight to the bar, whereat he noticed two others sitting, but couldn’t make them out until his eyes adjusted to the dark.

“Whiskey and a beer,” he said to Roof, the tall half-Indian bartender.

“Right up, Bill,” said Roof.

Bill lit a cigarette, glanced to his right, took a drag and said, “Jackpot.”

Roof set down Bill’s drinks and shifted his eyes over to the two lost souls sitting at the bar to Bill’s right, then glanced back at Bill. Next to Bill was a slumped over man in his late fifties or early sixties, a near empty mug in front of him, his fingers curled around it. Next to that man was a very small, prematurely shriveled woman in cutoff denim shorts, a striped tank top and flip flops. Enid Pound. Bill was taken by how quiet it was in the place.

Bill set his cigarette in the ashtray groove, did his shot of whiskey, and fished a dollar bill from his pants pocket, got up and walked over to the jukebox, which was lit up like Vegas, desperate for a few songs. But when he got closer to it, he realized the jukebox was busted up. Big chunks of the jukebox’s plastic dome were broken off and there were cracks in it. It was still blinking and flashing, but he paused before putting his money in. He also noticed that to the right of the busted up jukebox was a chair, one leg broke off, leaned up against a post.

“What happened to your jukebox, Roof.” He said, putting the dollar back into his pocket.

“There was a fight. Jukebox lost.” He chuckled and glanced at Enid, who was also chuckling, but hers was more of a wheeze.

“Does it still work?”

“I gather it don’t,” said Enid, turning on the bar stool and facing the sheriff. She propped her elbows up and leaned back against the bar.

“Enid Pound—that you?”

“You know damn well it is.”

“You’re just the woman I was hoping to run into today.”

“Sure are popular with sheriffs today,” said Roof.

“What’s that, Roof?” said Bill.

“Old Frank was just in here about an hour ago,” said Enid. “He’s retired, but don’t act like it. Finding it difficult to enjoy the autumn of his life.”

“I bet I know why,” said Bill.

“Don’t take a rocket surgeon to figure out,” said Enid.

“Reckon you and I can have a chat ourselves?”

“My policy on talking to the authorities in a drinking establishment is simple.”

“Let me guess: I buy, you talk.”

Enid smiled and walked over to Bill, still standing by the dilapidated jukebox, and they both sat down at a nearby table. As they sat, a gust of wind drove rain at the tin roof of the bar, making a loud racket.

“Ooh,” said Enid. “I love it when the weather is hostile, don’t you, Sheriff?”

The drive to Leon Bradford’s ranch from the station was about thirty minutes. Lloyd went over what he would say, what he would ask, what he would look for. Brahmans missing—Walter missing. Two facts with a lot of open air between them. He also knew that Bill would not have approve of this trip to Bradford’s. Bill did not approve of “hunches” and “gut feelings.” Bill was a hard-facts man, a cautious and thoughtful man. Lloyd respected Bill immensely, but Lloyd had his own ways and they had not yet failed him in a major way so he had no reason to second guess himself.

The double track up to Leon’s home on the back of the property was partially canopied and Lloyd found himself driving slowly to savor the dark, cool atmosphere, a scene, he thought, right out of a story about Robin Hood or King Arthur. It was one o’clock now and the sun was high and it was hot and humid, when not under the heavy shade of old-growth. But there was the hint of a storm in the north. He noticed fresh tire tread marks in the dirt and wondered if the Bradford’s were even home.

When Lloyd emerged from the cave of trees onto the lawn of Leon’s home he was somewhat surprised to find Leon and Michaela outside. Leon stood with his hands on his hips, looking down at something Lloyd could not quite make out, and Michaela was pulling a water hose around the right side of the two-story redbrick home. She eventually was out of his view. Leon didn’t so much as glance Lloyd’s way until he was out of the truck and walking towards the house.

The thing on the ground in front of Leon turned out to be a dead whitetail doe.

“Jesus,” said Lloyd, as he walked up to Leon.

“Damnedest thing.”

“Looks fresh.”

Leon grunted.

“How is it that you’re just coming across it then?”

Leon finally looked over at Lloyd.

“What you doing here, Deputy?”

“Wanted to talk to you about them Brahmans stole.”

Leon nodded, pointed behind him.

“Michaela and I just got back from town not ten minutes ago. Left here—shoot—around eight, and I don’t recall seeing it here then.” He scratched at the crown of his head.

“Looks like it just dropped dead, don’t it?” said Lloyd. He knelt down and gently put his hand to its neck.

“What I thought.”

Lloyd wondered if a doe could have a heart attack or a massive stroke.

Michaela came back around with her water hose.

“Deputy,” she said.

Lloyd and Leon stopped to watch her. Leon smiled at her.

“What you doing lugging that hose all over the yard for?”

“Just watering.”

“Leon, you too cheap to have some irrigation put in for your wife?”

“Says she likes the watering. Gives her something to do.” Leon turned back to the doe. “You help me pick her up and put her in a wheelbarrow?”

Bill watched Enid take a sip from her new mug of beer and watched her light a slightly bent cigarette she’d pulled from a crumpled soft pack of generic cigarettes.

“Walter’s candyass cousin still working for you?” said Enid, blowing a cloud of cheap smoke.

“Lloyd still does, yes. Wouldn’t necessarily call him a candyass, though. He ain’t the brightest star in the sky, but he’s a tough son of a bitch and a loyal officer of the law.” Bill wasn’t being funny. He meant what he said.

Enid grinned a toothless grin and coughed a quick laugh.

“Okay,” she said. “Guess you don’t know him like I do.”

“Being that he’s a Pound and you’re a Baggott, I wouldn’t think you knew him much at all.”

“I am married to his first cousin—and I’ve heard all the same stories as everyone else in this part of the world, except I’ve heard the real versions.”

“Real versions? You mean your and Walter’s versions?”

“The realest versions.”

She smeared out her cigarette and skated the mug of beer around in the condensation puddle on the table.

“Speaking of Walter,” said Bill.

Enid looked him in the eye, and Bill winked.

“You find out anything about his whereabouts?”

“Not precisely.”

“Let me get this right. You’re talking to the person who reported him missing to try and find out where he is? That don’t make a damn bit of sense, does it?”

“It does if you know what I know.”

Enid finished her beer and lit her flattened, bent last cigarette.

Bill held up two fingers and Roof turned around and grabbed two clean mugs.

“Go on, then.”

“First I want to ask you a few serious questions. No more of this playing around.”

“Who’s been playing? You ask, I answer.”

“It’s just that, if you really want to know where Walter is, you’ll want to answer me true. I don’t give a good goddamn about Walter. He could fuck right off, as far as I’m concerned. He could trip over and fall off the edge of the Earth, and I wouldn’t even spill my drink. And to be honest: whether he’s alive or dead or somewhere in between—that don’t really matter to me, neither. But it’s my job to figure things out. So let’s you and me figure this shit right here out.”

Enid put out her cigarette and crossed her arms and sat back in her chair.

Bill leaned in, put his elbows on the rickety table.

“Walter do something to severely piss off any of these bikers we got around these parts?”

“You got some paper and something to write with? We’ll make a list.”

Bill sighed and leaned back. “Anything lately or serious and longstanding—anything that might stand out in your mind?”

“He’s got some outstanding debt with them Evil Dead pussies. But they like having a little debt on you so they can get you to do shit for them to supposedly ‘cancel’ that debt, which never actually happens. They scumbags, but they ain’t stupid, least not the ones running the show.”

“You talk like you know about Walter and his dealings with folks.”

“Walter wouldn’t make a left turn without I told him ready on the right.”

“Got him trained, do you?”

“He’s just smart enough to know he’s stupid, is all.”

“So he consults with you on every little thing then?”

“Every little important thing.”

“Then you’ll know the answer to this question, I reckon: did Walter steal Leon Bradford’s Brahmans?”

Enid smiled.

“I’ll answer that question. I’ll answer it thoroughly. But first you answer a question for me.”

“Fine.”

“You think you know what happened to him, where he is?”

Bill figured he was in a good spot here, tactically, and decided that telling her the truth would make her angry, put her right in his hands, get her to talk wide open.

“This morning, in one of Parson’s lemon groves, offa twenty-seven, we found a body. A burnt up Walter-sized body.”

“But you don’t know it’s Walter.”

“Well, the body ain’t exactly…pristine. The body ain’t exactly recognizable.” Bill looked at his watch. “Matter fact, medical examiner probably just now finishing up with it. I’ll make a call, soon as we’re done here, and I’ll let you know on the spot what they tell me. But, right now, I want to know what you know.”

Enid lowered her head and Bill thought she must be crying. Her shoulders jerked a few times. She then held her head up and took a deep breath, looked back at Bill, eyes aglow, brow set.

“Walter did steal that crazy fucker’s cattle. Stole the shit out of ‘em. But seeing how Walter don’t own a fucking tea towel, he had to line up some help. And that help, I reckon, fucked him.”

“Go on.”

“Walter had the idea of using a couple side-by-sides, corralling as many as they could into a semi-trailer, and hightailing it. In and out. Wee hours. Only Walter, like I said, ain’t got shit. So he went to that Evil Dead dick Douglas. He and some other asshole got the side-by-sides and the semi and trailer and they pitched in on the job. Douglas had another ‘friend’ of his rebrand the cattle and take them to auction. Got top dollar, too. They sold them Brahmans and didn’t give Walter a red fucking cent. About two days after that I lost track of Walter.”

“So you do think Douglas and his bunch killed Walter.”

“You asked me if he stole them Brahmans. I told you he did and told you how they did it. I didn’t say word fucking one about who I think killed Walter. But since you brought it up, I’ll tell you what I think for free.” She paused and glanced to the left. “I need to take a trip to the little girls’ room.”

“You ain’t gonna run off, are ya?”

“What the hell for? But there better be a fresh one on the table when I get back.”

“Thought this one was gonna be for free.”

“Reconsidered. Nothing worth having is free.”

When she returned, Bill offered her one of his cigarettes. She took it, lit it, and took a long pull on the new beer in front of her before beginning.

Bill held up two fingers again and Roof hustled over two more mugs of beer.

“Thing is, you cain’t never be too sure with these waterheads we share blood with. Why Walter and I moved out here to Cortez. We still close, but far enough that we ain’t having to constantly worry.”

Bill and Enid sat and sipped for a while. Bill was perplexed. If Enid was telling the truth, he wasn’t sure how to proceed. He lit a cigarette and noticed Enid watching him. He reached his pack across the table and she took another one from the pack.

“Winston’s,” she said. “Fancy.”

He watched her take a match from a folded-up matchbook and slowly drag the match across the ignitor strip. She help up the match and looked at Bill, then lit her borrowed cigarette.

After exhaling a drag that seemed to consume half the cigarette, Enid spoke.

“What about Leon. You go and talk to Leon and Michaela about any of this?”

“What do you mean, what about Leon and Michaela?”

“Leon is a sad bastard—but you cain’t imagine the shit Michaela’s managed to do without any law finding out. She’s small but she’s cunning and she’s a nasty little bitch. Leon wouldn’t hurt a yellow fly but Michaela—being married to Leon is like a mask of respectability. She’s shady.”

“Sounds ridiculous,” said Bill.

She smiled as she smashed her cigarette butt into the ashtray.

“She likes it that you think so.”

The deer was not heavy but it was somewhat difficult to pick up and maneuver into the wheelbarrow.

“Got a roll-off around the house,” said Leon.

Lloyd followed Leon. They walked by the garage, door open, and Lloyd admired Leon’s old caddy, a fifty-nine.

“You’ll have to take me for a ride in that beauty one of these days.”

“How about today?”

Lloyd did not respond as they were at the roll-off and Leon had set the wheelbarrow down next to it.

“I guess,” said Leon, “just take your side and I’ll take mine and we’ll hoist her up and over.”

It was quick work and as they were walking back to the garage to put away the wheelbarrow, Lloyd remembered why he was there.

“Anyway,” said Lloyd. “I was meaning to ask you about them Brahmans you had stole last week.”

Leon nodded.

Michaela came around the corner, into the garage.

“Y’all done with the ‘barrow?”

Leon said yes and she picked up a bag of Black Kow and dropped it into the wheelbarrow with a grunt, then wheeled it off. She was a little younger than Leon, and she was strong for her size, too, which Lloyd guessed to be about five-foot-three.

“Have y’all made any progress on the case?” said Leon.

This question almost startled Lloyd and it took him a few seconds to answer.

“No sir, but I wanted to ask you some questions.”

“That’ll be fine,” said Leon.

“I know you and Michaela ain’t ones to get mixed up in all this Pound-Baggott garbage—as you know, I ain’t either—but I still wanted to ask you if you was aware of anything that might have passed by me. As far as I know, things have been fairly quiet lately.”

“Well, hell,” said Leon. “You’d know more than Michaela and me. We’re far removed from all that fighting and whatnot."

Lloyd nodded. He was beginning to become aware of a sound behind him, a thumping-whirring sound, that seemed to be coming from all directions.

“That’s what I figured, too,” said Lloyd. He turned and saw a helicopter coming closer. “I had to ask, though.” He had to talk louder, as the helicopter was quite close now. He looked at Leon and Leon grabbed his shoulder and pointed towards the front of the house. Leon’s hair was raised up now and he squinted.

They both jogged to the front yard.

“Leon—why’s a goddamn helicopter landing in your backyard?”

Leon smiled nervously, his demeanor somewhat changed.

“Michaela has always been fascinated. Always wanted to learn.”

“Learn what—to fly a fucking helicopter?”

“Yes, that’s right. She’s taking lessons.”

“From who?”

“That Sugar—Parson’s boy.”

“Where’d he learn to fly one?”

“Air Force, I reckon.”

An idea was beginning to form in Lloyd’s mind. It wasn’t all joined up yet, but there was enough. He thought about how the body at Parson’s lemon grove seemed to have been laid there by magic. And Sugar had allegedly found it.

Keep calm, he told himself.

“Well I think that’s great,” he said. “Good for her. Man, how’s she coming along? I bet it’s complicated. I know it’s hard to learn.”

“Oh, pretty good.” Leon’s hands were in his pockets now.

“How many lessons she have so far?”

“Not sure, a few.”

Bullshit, thought Lloyd. If she were taking lessons, they’d be expensive—he’d know exactly how many she’d taken. Course he might just be nervous. I need time, thought Lloyd.

“Anyway, I wanted to ask you—you got any idea who might have stole your brahmans? Just thought I’d ask. Wasn’t sure if anyone had asked yet.”

“How the hell should I know, Lloyd? Don’t you think I’d have told you something like that, if I had an idea?”

Lloyd could barely hear anything but the helicopter now. He gave Leon a smile and a thumbs up.

They both stood and watched the helicopter hover in the air, just above roof-level. Sure enough, it was Sugar piloting the thing.

Michaela bent over, scrambled up to the helicopter.

Leon waved, Lloyd did too.

Michaela and the man both waved back. After a few seconds, she walked around and got in the passenger side of the helicopter. The helicopter slowly turned and, as it turned, floated higher upward, then it moved out towards the pastureland behind the Bradford home.

The sound of the helicopter faded and Lloyd got an idea.

“So, Leon, I think I’ll take you up on that ride in the Caddy another day.”

Leon nodded and smiled a little. Do I have enough, thought Lloyd? Bill would say that he didn’t, he knew that much. He thought about the medical examiner’s office—what had they found out by now? If it’s Walter’s body—and if he stole the cattle—and Leon knows….Would they have had Walter killed? Michaela’s a Baggott. Would have reason to hate Walter beyond the cattle thieving. Not poor old Leon, though. Surely not Leon.

As he walked back to his truck, it took everything he had not to turn around and cuff Leon and bring him in.

Lloyd made it about halfway down the long dirt drive from Leon’s house back to the road before he met up with Bill’s truck coming up the drive. He noticed someone in the passenger seat, someone small, the top of a head the only thing visible. He waved, and Bill pulled up alongside and Lloyd recognized Enid.

“We barking up the same tree, looks like,” said Lloyd.

Bill winked and glanced over at Enid.

“Medical examiner identified the Parson’s grove body as Walter Pound,” said Bill. “Dental records. My sympathies—to you both,” he added. “I know he was sorry but family is family.”

They all sat quiet for a moment. Enid spoke first.

“It’s Michaela what’s done it,” she said with authority, looked over at Lloyd.

“I think so, too,” said Lloyd. “Just watched her hop on a helicopter with Sugar and whirl away. Lessons they called it.”

Enid sat and listened whie the two men talked.

“I don’t reckon Leon knows the first thing about any of this, but Michaela and that Sugar Burkson bastard—I’d bet the farm they did this together.”

“For Michaela, motivation is there. The thievery and the family history.”

“Don’t forget the being crazy as a shithouse rat part,” said Enid.

Lloyd smiled at Enid’s comment.

“Enid, just thought of something,” said Lloyd, raindrops beginning to tap on their truck hoods.

“Hoyt Baggott was Michaela’s uncle, wasn’t he?”

She nodded. “And my first cousin,” she added.

“Well,” said Bill, squinting at the dark gray sky. “Starting up again.”

As the rain picked up, Lloyd waited impatiently for Bill to lay out their next moves. He told him to wait just off Bradford’s property for Michaela’s possible return by helicopter. Lay low and watch. Despite the rain angling in, Enid had not rolled up her window. Walters dead. Her man is dead. She seemed to be looking down at her hands, resting palms up in her lap, fingers curled inward, two dead spiders. Enid could have been someone, thought Lloyd, as Frank angled the truck into a three-point turn.

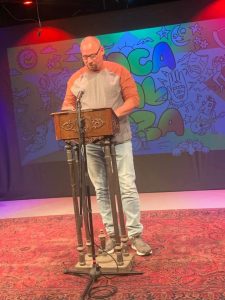

Steve Lambert was born in Louisiana and grew up in Florida. His writing has appeared in Adirondack Review, Broad River Review, BULL, Chiron Review, Contrast, The Cortland Review, Emrys Journal, Into the Void, Longleaf Review, New World Writing, The Pinch, Saw Palm, Tampa Review, and many other places. In 2018 he won Emrys Journal’s Nancy Dew Taylor Poetry Prize and he is the recipient of four Pushcart Prize nominations. Interviews with Lambert have appeared in print, on podcasts, and public radio. He is the author of the poetry collections Heat Seekers (2017) and The Shamble (2021), the chapbook In Eynsham (2020), and the fiction collection The Patron Saint of Birds (2020). His novel, Philisteens, was released in 2021. The collaborative fiction text, Mortality Birds, written with Timothy Dodd, appeared in 2022. He and his wife live in Florida.

Steve Lambert was born in Louisiana and grew up in Florida. His writing has appeared in Adirondack Review, Broad River Review, BULL, Chiron Review, Contrast, The Cortland Review, Emrys Journal, Into the Void, Longleaf Review, New World Writing, The Pinch, Saw Palm, Tampa Review, and many other places. In 2018 he won Emrys Journal’s Nancy Dew Taylor Poetry Prize and he is the recipient of four Pushcart Prize nominations. Interviews with Lambert have appeared in print, on podcasts, and public radio. He is the author of the poetry collections Heat Seekers (2017) and The Shamble (2021), the chapbook In Eynsham (2020), and the fiction collection The Patron Saint of Birds (2020). His novel, Philisteens, was released in 2021. The collaborative fiction text, Mortality Birds, written with Timothy Dodd, appeared in 2022. He and his wife live in Florida.